I woke up in an unfamiliar motel room in Kiev, Ukraine. Prior to arriving, I’d received special government permission to explore Chernobyl, the highly radioactive zone that became infamous in 1986 when a failed test resulted in a deadly meltdown in a nuclear reactor. While I thought I knew a lot about the disaster prior to visiting Ukraine, I really had no idea how magnificent the disaster had been until I experienced the fallout.

One of the first people I met in Ukraine was Ana, a woman in her 30s who had been born and raised in Kiev. She was tall, fair skinned and had fake blond hair. She brought up Chernobyl and said with a lot of confidence that she believed that the disaster was a problem so big and so spectacular that the disaster itself and the massive labor-intensive cleanup could only have occurred in the Soviet Union. Today, 32 years after the initial explosion, an estimated 17% of the entire area of Ukraine and a staggering 25% of all of Belarus are still considered to be contaminated with atomic radiation levels that are above the level that is safe for humans. The cleanup efforts under the USSR required the mobilization of a half a million people to bury, fortify and clean the worst hit areas. 10,000 miners were brought in to dig a tunnel under the affected reactor in order to try to build an apparatus to prevent highly radioactive magma from continuing to melt downward into the earth. Entire cities were abandoned in the course of hours and in one particularly short-sighted mistake, hazardous lead was poured directly onto the overheated reactor in an effort to create a casing. The lead instantly boiled, combined with extremely dangerous radiation and immediately floated through the air outwards toward the rest of Europe. It was a disaster to benchmark other disasters.

I traveled to Ukraine to explore the radioactive zone and to see for myself the three remaining functional reactors, each of which is in the beginning stages of a 65-year decommission process.

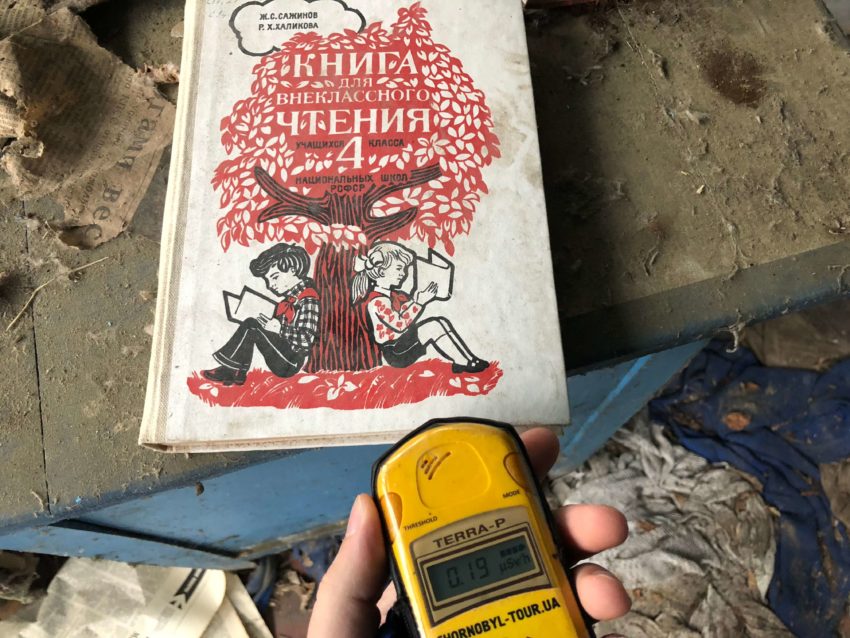

Atomic radiation is odorless, tasteless and visually invisible to humans. You can walk right into a lethal zone and not know it until later when your body starts to burn irreversibly from the inside out. At the time of the disaster, not even the nuclear physicists who were brought in to solve the problem could accurately predict how dangerously high the radiation levels were. The only available radiation dosimeters available immediately after the explosion did not have scales high enough to measure the true level of the radiation, The device readings maxed out and the experts had to try to guess what the levels might be. Many of those experts died several weeks later from their exposure.

So why would I voluntarily exposure myself to this kind of sadistic risk?

My day-trip to the disaster site came several months after I had officially finished every single one of my life goals. I was past the honeymoon period of completing my life mission and was on the verge of an impending existential crisis. Adventures had satiated my inner calling before so it was the only effective medicine I knew to avoid my own crisis.

After passing through several military checkpoints, our small group finally made it to what would become the most exciting surprise of the adventure, an abandoned military base on the outskirts of the reactor site.

In the years prior to the disaster, the USSR actively developed an absolutely massive experimental radar array system that was aimed at detecting over-the-horizon instances of inbound American intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). This predecessor to modern radar systems which was codenamed, Duga, was so powerful that it needed to be located near a nuclear power plant in order to meet its electricity needs. When operating, the array globally broadcast a sharp, repetitive tapping noise at 10 Hz which led to it being nicknamed by annoyed shortwave listeners the Russian Woodpecker. The signal was so problematic globally that some radio and television manufacturers of the era started included ‘Woodpecker Blankers’ in their circuit designs in efforts to block the signal.

Due to radiation exposure and the magnitude of the disaster at Chernobyl, the secretive radar array was forced to stop operations in the months after the reactor meltdown. The metal used in the huge installation was contaminated with radiation and is still dangerous to this day.

This array installation was the first major stop of our exploration.

Following having my mind rocked by the formally secret and now radioactive radar array, we headed to Pripyat, the now infamous city that was most heavily impacted by the nuclear meltdown.

Pripyat was founded as a special “nuclear city” within the Soviet Union. It was built largely as an exercise in showing how communism could produce a futuristic and luxurious city based on science and nuclear energy. At its peak, the city had a population of 49,360 and contained a stadium, a large public aquatic center, beautiful cafes and an amusement park.

Roughly 36 hours after the explosion of the nearby reactor, the entire population of Pripyat was evacuated. In a show of great Soviet might and efficiency, close to 2,000 buses were rushed in from surrounding cities and the nearly 50,000 person city was completely evacuated within three and half hours. Reports show the evacuation was non-violent and people remained unpanicked.

Afterward, the worst of the contaminated city (furniture, clothing, household objects, vehicles, etc) were buried or destroyed. Most of the buildings, including the now infamous amusement park, still remain.

Points of Interest From Pripyat And Nearby Towns

Exploring the apocalyptic town first-hand was the closest I have ever come to living inside a dream.

In a world full of highlight reels and 24-hour news coverage, seeing something truly astonishing has become a novelty, a moment worth aspiring for.

While exploring Cherynobl, every turn, every opened door, exposed me to something new and amazing. Moments of wonderment and unbridled amazement happened over and over again within the course of just a single day. I walked out of the city completely satiated.

In a world of abundant information, it is easy to fall into the trap of confusing information consumption with experiential nourishment.

Today, when a volcano erupts, a drone spaceship lands on an asteroid or a submarine dives to the bottom of the deepest part of the ocean, we can all watch, listen and read about the events as if we were the ones experiencing them. This is a great power and a remarkable positive step for humanity but it doesn’t release us from the need to actually experience wonderful adventures first-hand.

Unlike mere information consumption, venturing out past your own experiential limits can expose you to physical danger. Without the filter of editors, you may stumble upon something that you are not intended to see or feel. While the discomfort that marks this edge exists to keep you safe, it also marks the point where growth and real nourishment begins.

We live on an astonishing planet that has experienced an absolutely incredible history. By all means, spend time reading about it, listening to reports about current events and watching movies about our shared humanity. But don’t forget, information consumption does not fulfill all of the needs of experiential nourishment. Every once in a while, take a step beyond your limits and be sure to actually experience this crazy world first-hand.

End Note: While I was exposed to higher than normal radiation during my visit, the exposure was not enough to cause any permanent damage. As you would expect, we took multiple precautions to protect ourselves.